A sense of historical perspective

✎ 8 mos agoI recently read Arundhati Roy’s the god of small things for the first time, which I enjoyed and reckon I might reread in the future. It inspirited me to muse on the past — places, cultures, histories — and on the present, too. What’s changed, and what hasn’t, where and why(?).

One of my favourite parts of the book is where Chacko narrates a brief history of planet Earth to the twins:

Then, to give Estha and Rahel a sense of Historical Perspective [...], he told them about the Earth Woman. He made them imagine that the earth—four thousand six hundred million years old—was a forty-six-year-old woman—as old, say, as Aleyamma Teacher, who gave them Malayalam lessons. It had taken the whole of the Earth Woman's life for the earth to become what it was. For the oceans to part. For the mountains to rise. The Earth Woman was 11 years old, Chacko said, when the first single-celled organisms appeared. The first animals, creatures like worms and jelly fish, appeared only when she was forty, She was over forty-five—just eight months ago—when dinosaurs roamed the earth.

“The whole of human civilization as we know it [...] began only two hours ago in the Earth Woman's life. As long as it takes us to drive from Ayemenem to Cochin. [...] the whole of contemporary history, the World Wars, the War of Dreams, the Man on the Moon, science, literature, philosophy, the pursuit of knowledge—was no more than a blink of the Earth Woman's eye.”

— Arundhati Roy, the god of small things (pp. 52-53)

This made me curious: about the accuracy of Chacko’s figures, and especially about oceans and mountains. So I decided to indulge an exploration of this, in a wolfram-notebook.

Age of the earth

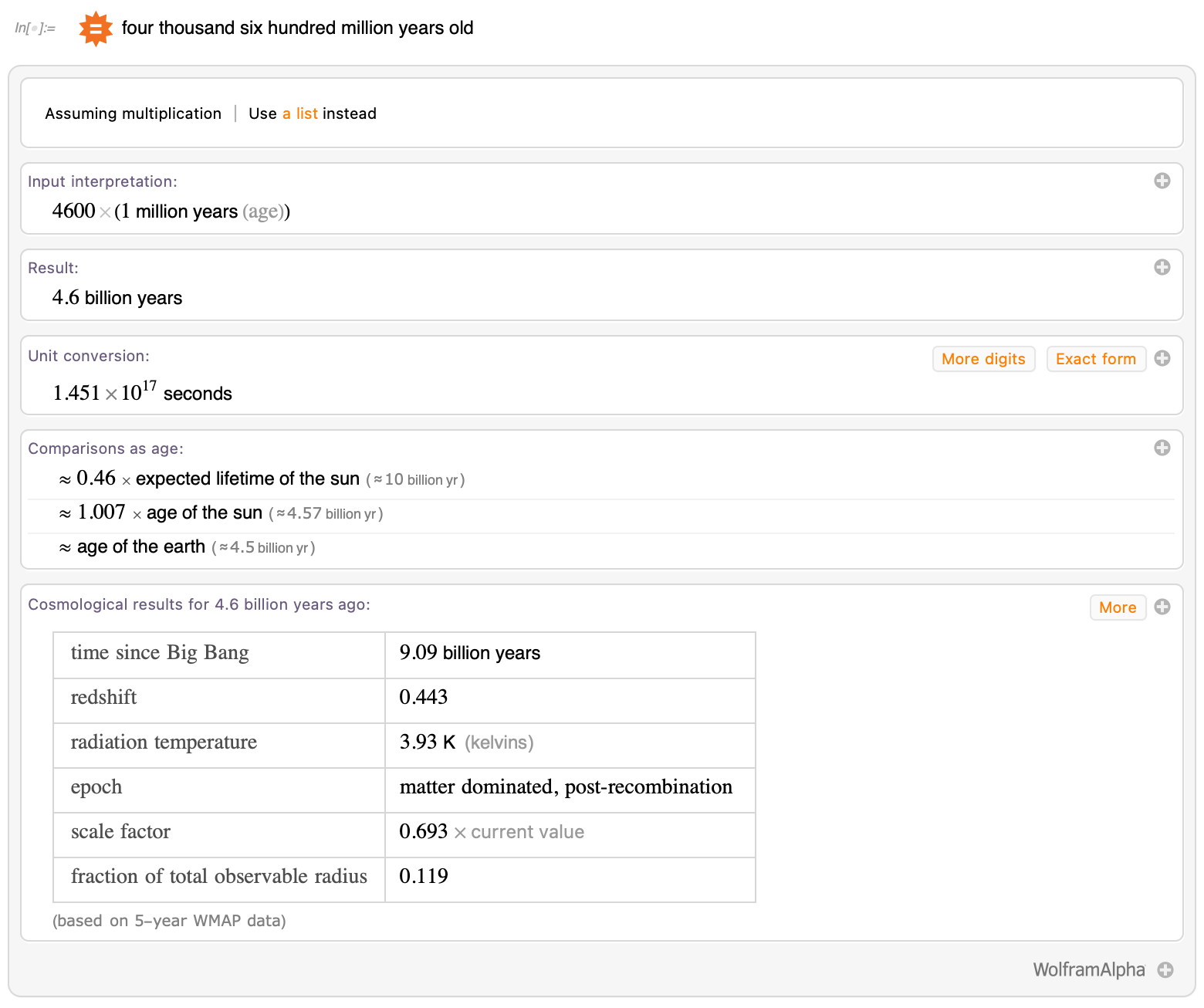

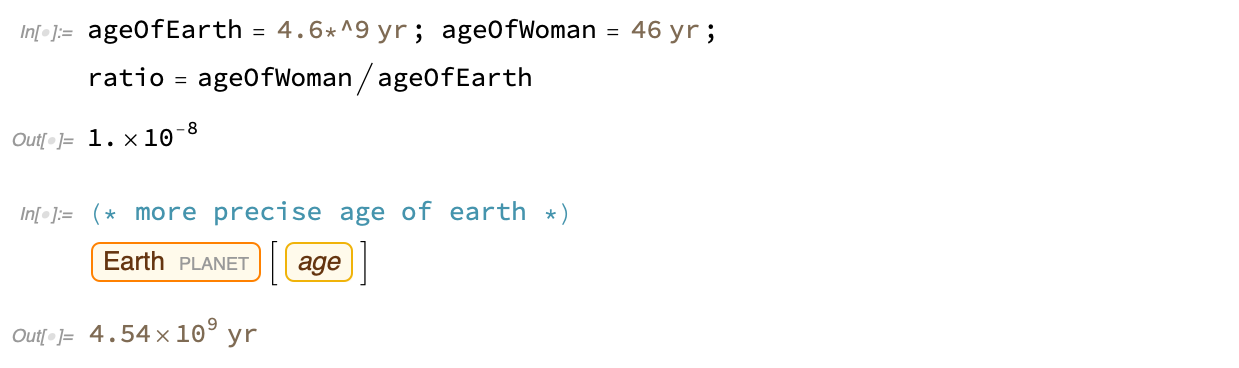

The earth, according to Chacko was four thousand six hundred million years old (which is 4.6 billion years, and approximately correct).

And Earth Woman’s age is ten-billionth of earth’s age.

Oceans

“We're Prisoners of War,” Chacko said. “Our dreams have been doctored. We belong no where. We sail unanchored on troubled seas. We may never be allowed ashore. Our sorrows will never be sad enough. Our lives never important enough. To matter.”

— p. 52

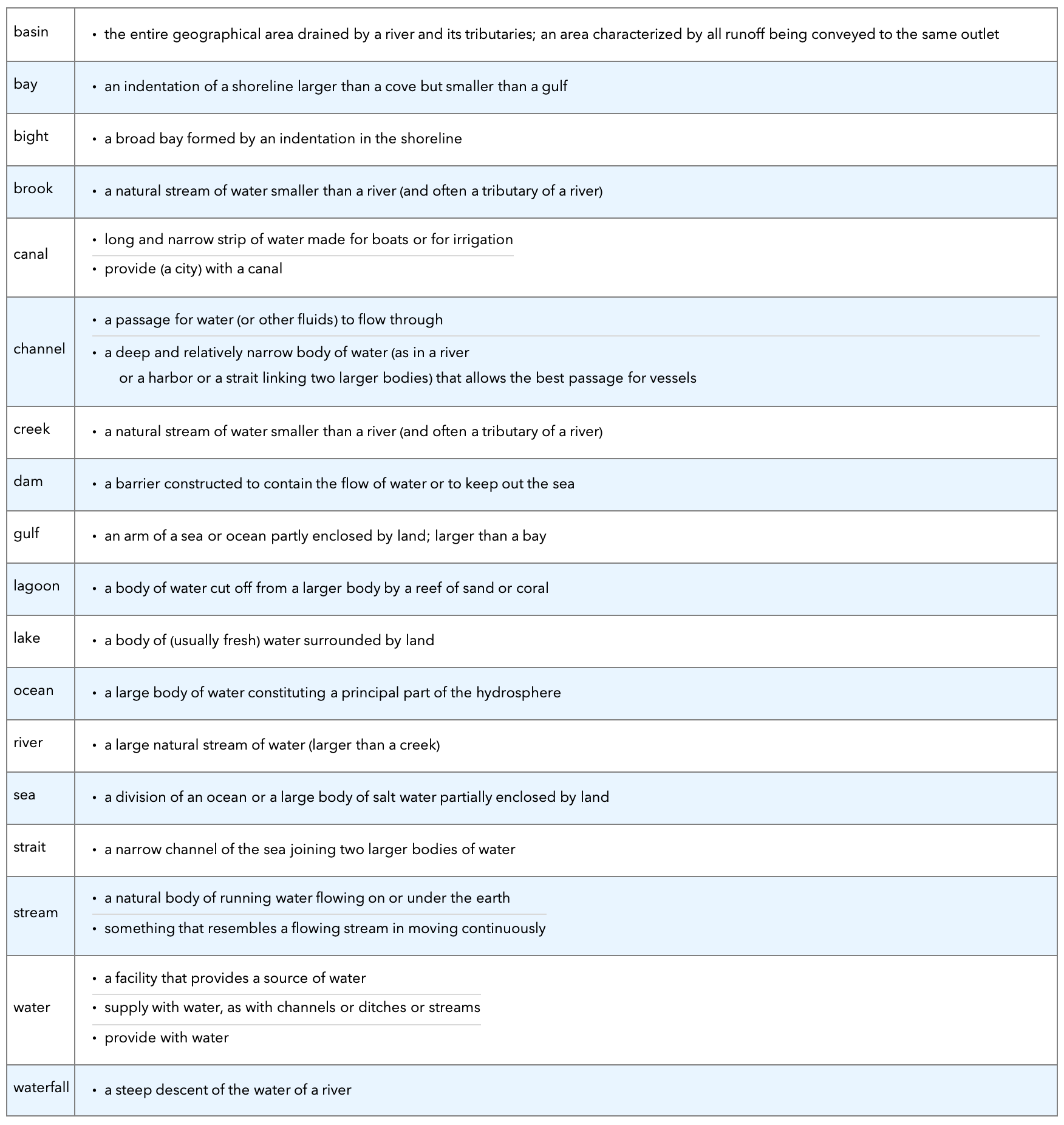

Definitions, first. Here are the (relevant) definitions of words related to oceans. I’m selecting only definitions which contain at least one of the other words in the word list.

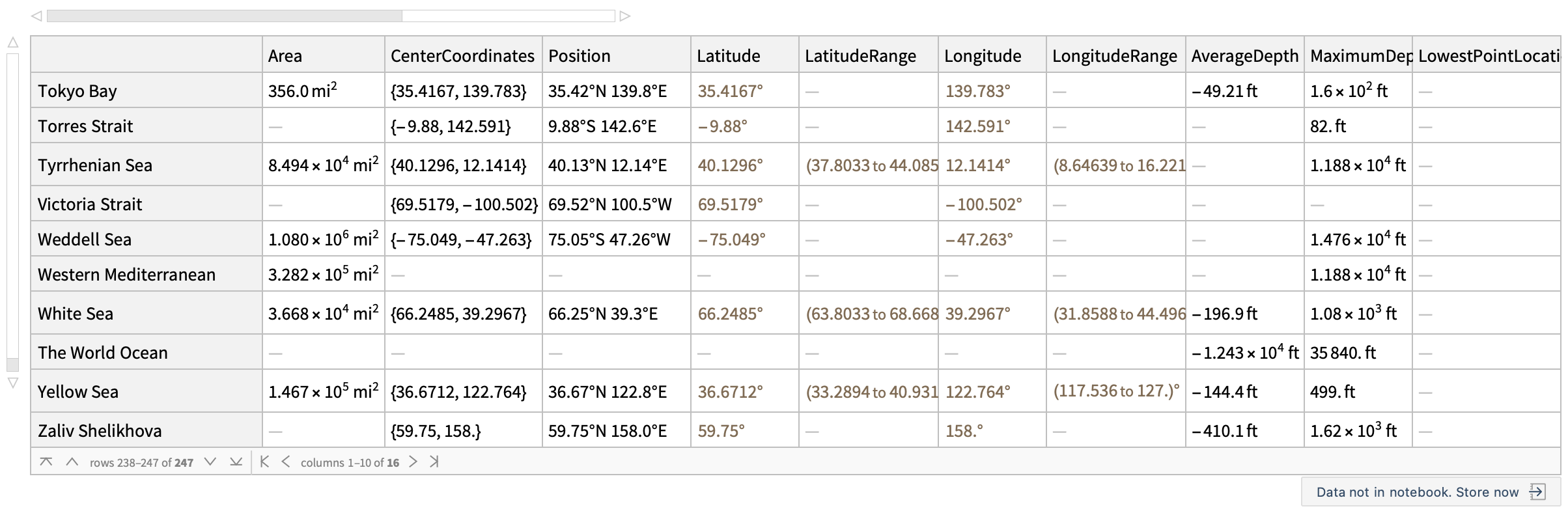

One can use OceanData to retrieve a dataset of world oceans and other water bodies that flow from them. Note that this isn’t a complete list of all water bodies around the world, but it’s an extensive one nonetheless.

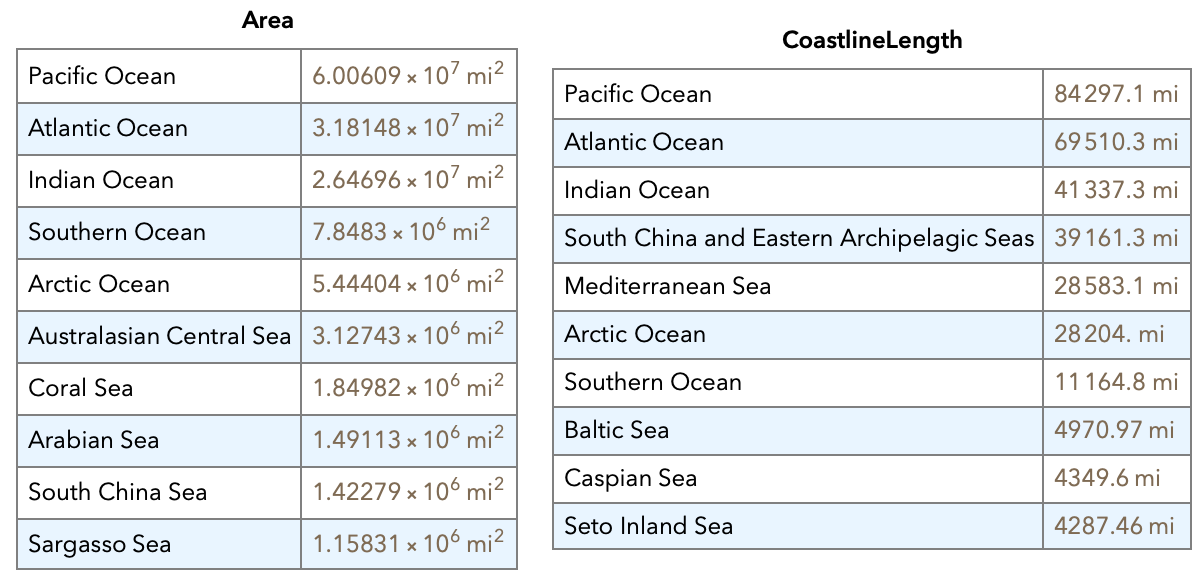

I now have a dataset of 247 water bodies and 16 properties for each one. Of course, there are some missing values, but there’s still enough for an interesting exploration. Here are the top ten rankings by some of the columns.

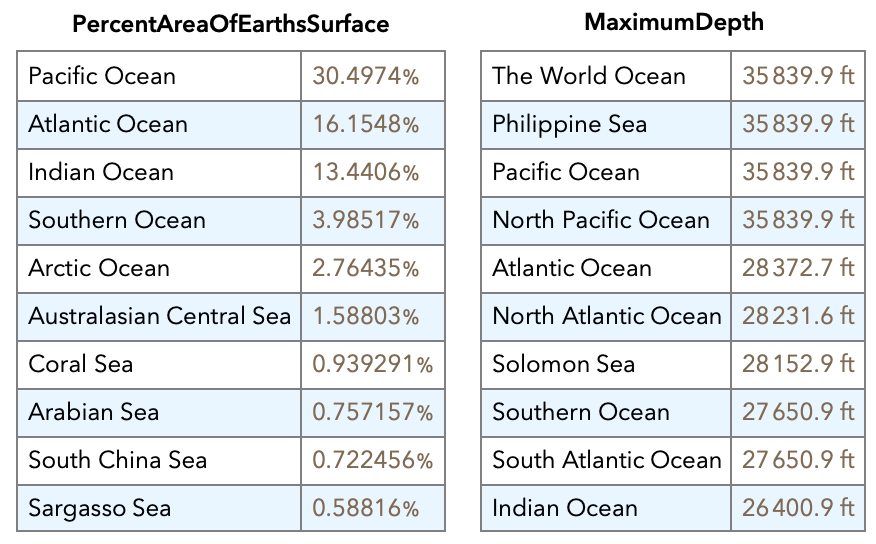

What do all these numbers mean? Let’s turn them into figures — this may give us a better perspective. This map shows the coverage of the oceans and seas:

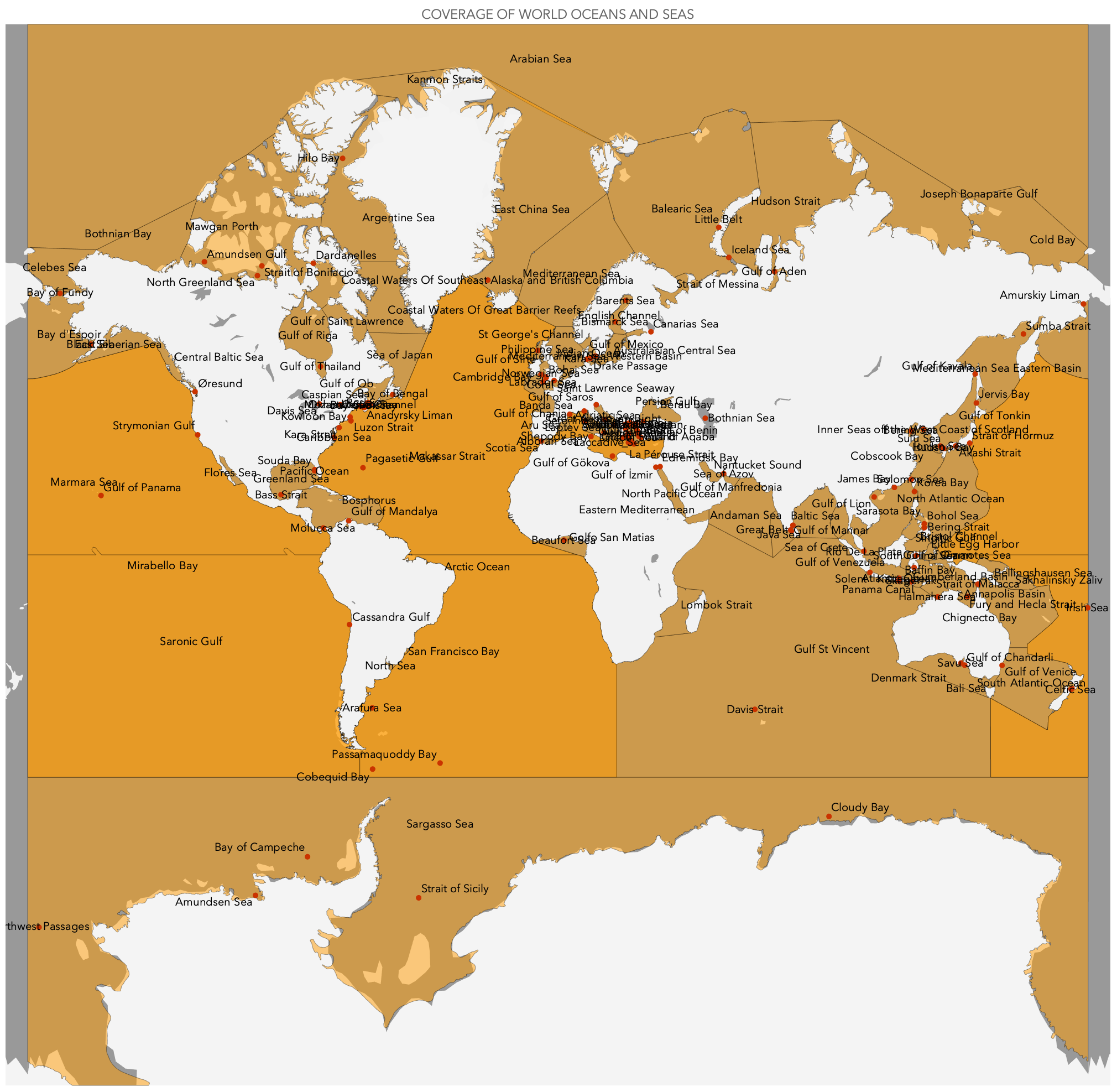

This map shows the elevation of the world, and it shows that earth is more or less as high as it is deep:

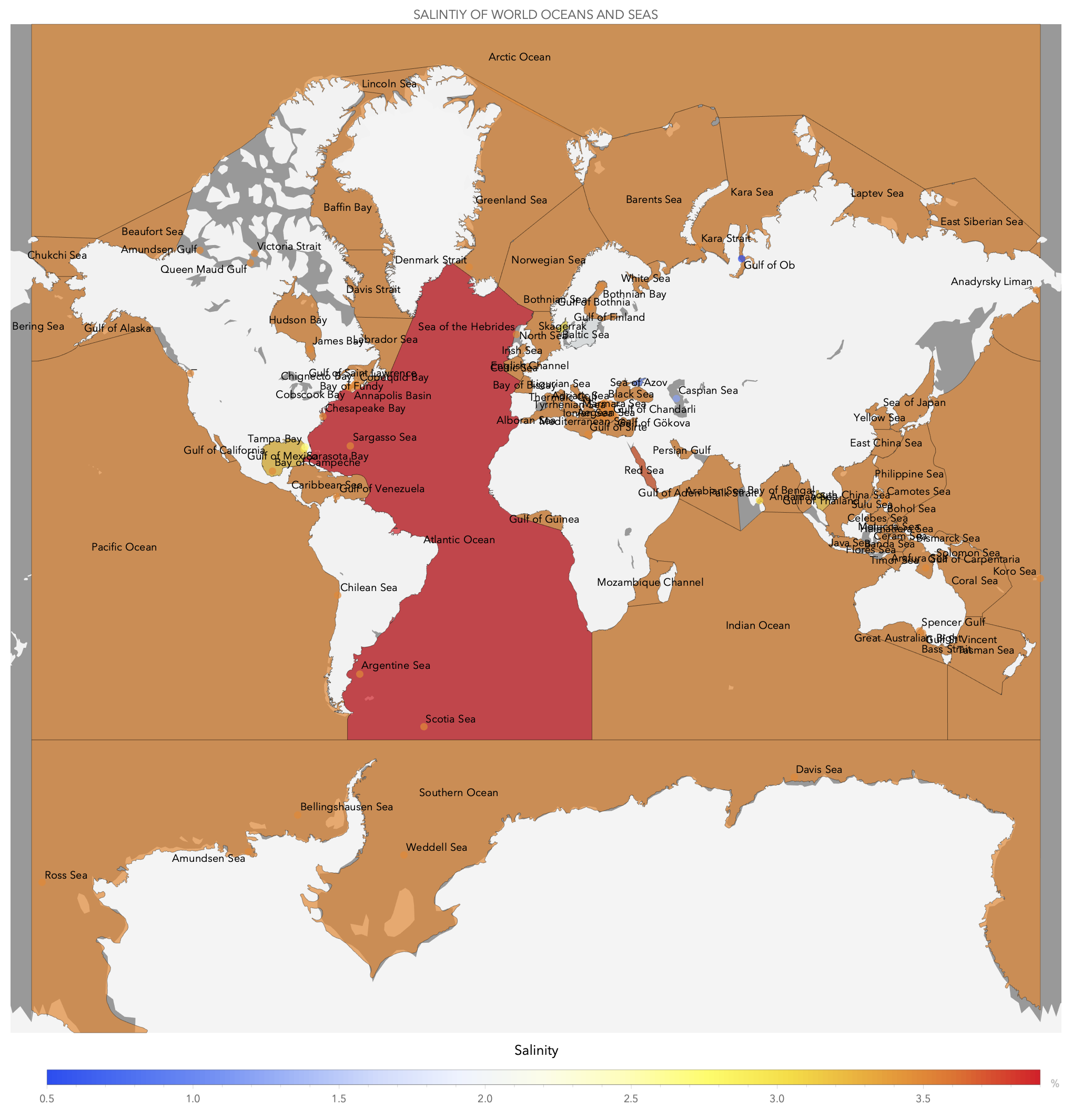

The map has a resolution of 20 contours, so it can be more detailed than it currently is. But you can see Mount Everest. This map shows the salinity of some of the water bodies (some values are missing in the dataset):

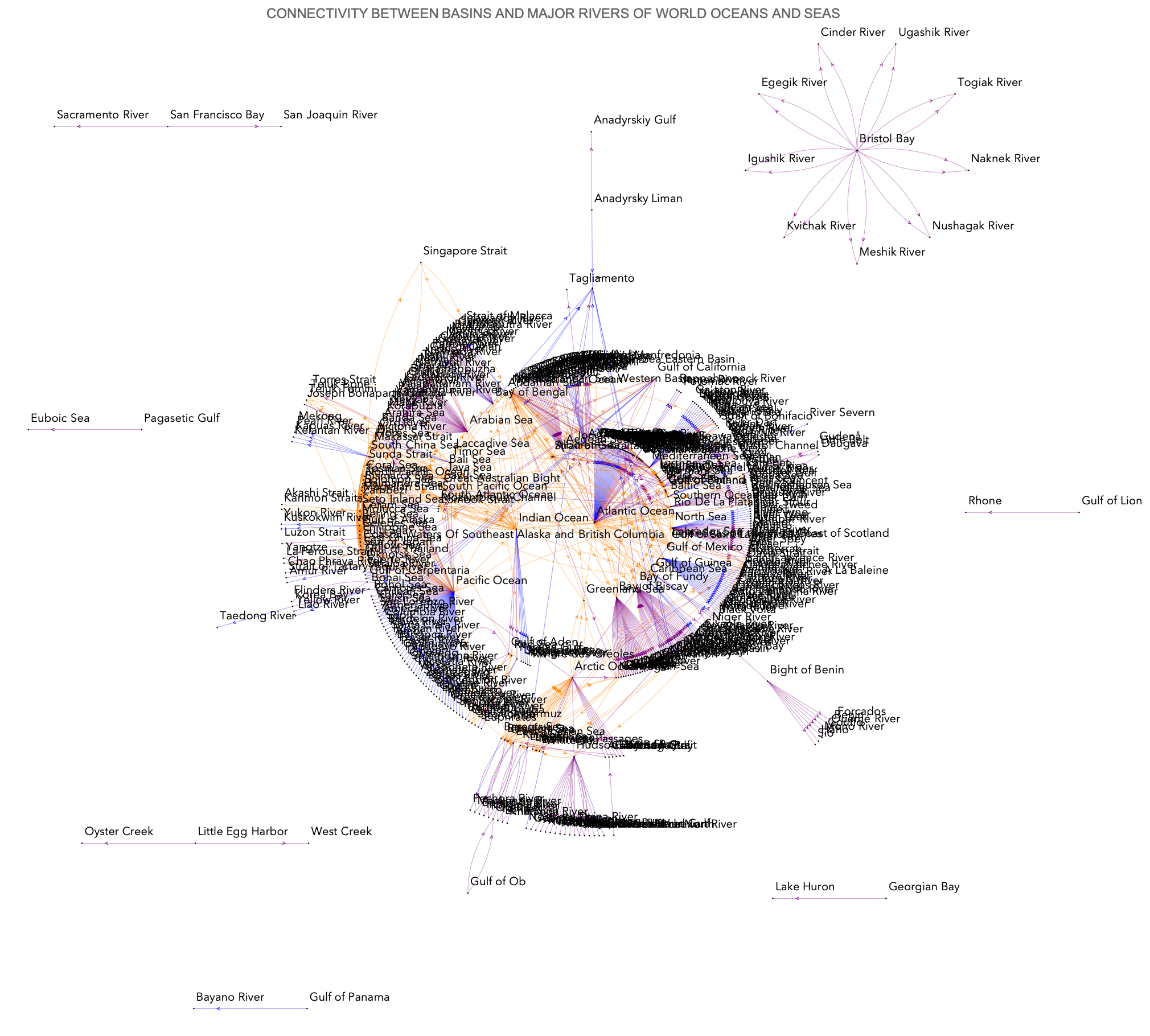

For each ocean, we can get its bordering bodies of water and basins (bights, seas, straits, etc.). And for each sea or whatever, we can get its basins and major rivers. So we can create a graph of the connectivity/adjacency between water bodies:

The orange edges show connections between oceans and seas. the purple ones connect oceans/seas to basins, while the blue edges link oceans to their major rivers.

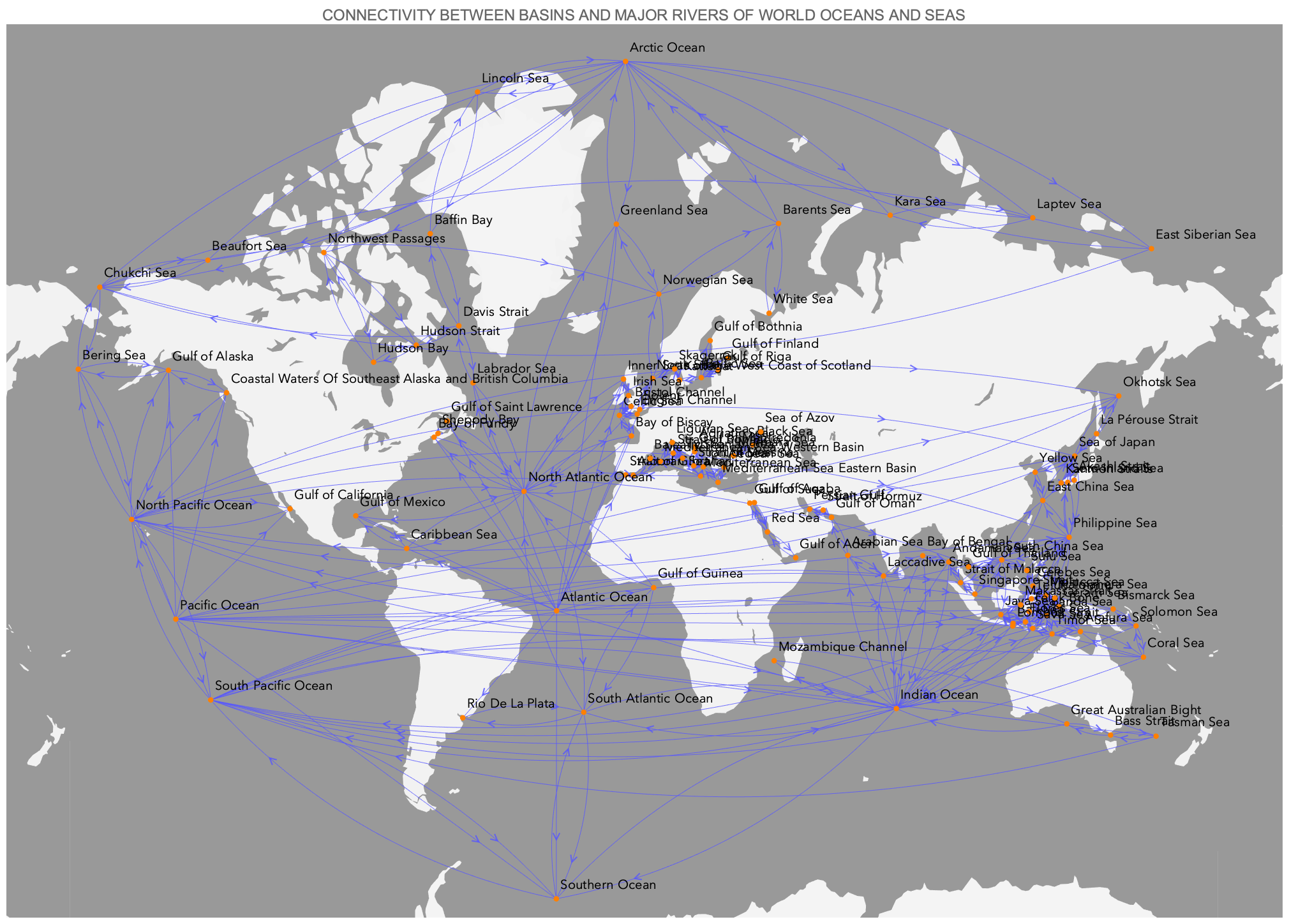

We have precise centre geo-coordinates for the oceans and seas, but not for rivers. We can plot this graph on a map to show the relative positions of the vertices:

In the map above, an arrow points from A to B, if B is a bordering waterbody, or a basin, of A. Remember that this does not include rivers, but I’ll return to those later on.

The motive for all this is to better understand how the water bodies on earth relate to one another. What flows into what; where and how quickly? Those kinds of questions. Luckily, we’ve got some data on rivers that’s useful, e.g., information on discharge, drainage, source, outflow, etc. Again, there are some missing data points, but hopefully, there’s enough to learn something new and interesting from.

TBC.